Table of Contents

ConstitutionsofWeb3

By Joshua Tan, Max Langenkamp, Anna Weichselbraun, Ann Brody, and Lucia Korpas

- Introduction

- Part I: Digital Constitutionalism and Web3

- Part II: Analyzing DAO Constitutions

- Part III: Towards Computational Constitutionalism

You can find the full, comment-enabled version of the paper, including the guide and template, here.

Abstract

The governance of online communities has been a critical issue since the first USENET groups, and a number of serious constitutions—declarations of goals, values, and rights—have emerged since the mid-1990s. More recently, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) have begun to publish their own constitutions, manifestos, and other governance documents.

There are two unique aspects to these documents: (1) they often govern significantly more resources than previously-observed online communities, and (2) are used in conjunction with smart contracts. These smart contracts enable computational governance, where certain community rights and processes are secured through code.

In this paper, we conduct an analysis of 19 DAO constitutions, observe a number of common patterns, and provide a set of recommendations to support the crafting and dissemination of future DAO constitutions. The text of these constitutions vary from 300-word blog posts to to 30-page legal charters, reflecting the variety of intended audiences, maturity of community, and document purpose. However, despite their differences, each constitution can be productively understood as part of a broader discourse around governance within the emerging DAO ecosystem.

Note: this paper is an interim report from the Constitutions of Web3 project by Metagov. We are still actively collecting and coding additional constitutions in order to validate our analysis and recommendations. If you are interested in contributing a constitution to our repository, please fill out the form at https://metagov.typeform.com/constitutions or get in touch with us at hello@metagov.org

Introduction

A decentralized autonomous organization, or DAO, is an online community partly organized by one or more smart contracts. Some of these smart contracts are quite simple, with only a treasury. Others are more sophisticated, with governance processes such as quadratic voting or conditional timelocks.

Smart contracts mark a departure from traditional governance documents. Traditional documents such as textual constitutions or policy statements can have strongly associated norms, however smart contracts will directly enforce rules. For example, if xDAO creates a smart contract that requires at least five people to approve a proposal, all proposals to xDAO with less than five people will be automatically rejected.

Although smart contracts are promising and increasingly important, they alone cannot govern communities; traditional constitutions and declarations of rights are still crucial for good governance. First, rights within smart contracts tend to only be relevant for a small set of transactions, each of which requires highly legible data

This essay aims

- to understand and contextualize the usage of written constitutions and smart contracts within the emerging politics of DAOs

- to analyze these textual documents in their own right

- to develop a stable set of principles and practices for future DAO constitutions.

The paper proceeds in four parts. In Part I, we review the history of digital constitutionalism on the internet. In Part II, we describe the rights, values, and goals of constitutions of Web3 and analyze some of the stylistic and political patterns we found. In Part III, we identify future directions for this research, focusing on work to analyze existing governance smart contracts to understand the types of rights and affordances that have (and have not) been written into them.

Part I: Digital Constitutionalism and Web3

The early internet hosted a number of notable constitutions and governance proposals. For example, Redeker, Gil, and Gasser (Redeker et al., 2018) collected and analyzed an extraordinary collection of constitutions and manifestos over the history of the internet, ranging from the early Rights and Responsibilities of Electronic Learners in 1992 to 2014’s Magna Carta for Philippine Internet Freedom. They describe digital constitutionalism as “a constellation of initiatives that have sought to articulate a set of political rights, governance norms, and limitations on the exercise of power on the Internet” (Redeker et al., 2018, p. 2).

Redeker et al.’s data set focuses on constitutions that assert rights and norms over the entire internet and/or key aspects of its infrastructure. Despite their emphasis on rights, most of these documents can be better understood as political declarations rather than as authoritative governance documents. By contrast, online communities throughout the history of the internet have enacted their own constitutions, which are more comparable to the governance documents of neighborhood associations or the charters of corporations. For example, early USENET groups (similar to many forum-based communities today) often posted a charter that described the intention and governance of that community, and open-source software communities such as Python have adopted similar governance procedures that articulate the rules and expectations for participating in these communities in comprehensive detail.

More recently, the development of blockchains and other cryptographic protocols have enabled the rise of a series of services and platforms collectively referred to as Web3. These technologies revolve around trustless mechanisms for social, economic, and political coordination. Many proponents of Web3 like to emphasize that typical forms of human governance (such as votes and constitutions) are not necessary or even desirable in Web3 communities

Decentralized autonomous organizations, or DAOs, have become an increasingly prominent form of digital institution in Web3. While the term is used differently in different communities, all DAOs embody certain institutional rules within code.

Taking inspiration from Redeker et al.’s survey of internet constitutions, we study governance in Web3 through the lens of digital constitutionalism. What follows is a set of preliminary findings from an analysis of the governance documents from 19 different decentralized organizations.

Data set and methods

In gathering the raw data, we collected publicly-available constitutions and governance documents from a range of representative DAOs including large protocol DAOs, service DAOs, investment DAOs, and NFT DAOs, with an emphasis on covering a wide range of institutional types rather than the biggest or most well-known DAOs. Our data collection was limited by the fact that many major DAOs do not have obvious constitutions, though almost all describe some form of governance process beyond the smart contract. The raw data set is housed in a publicly available GitHub repository. Data collection is ongoing as of the publication of this report.

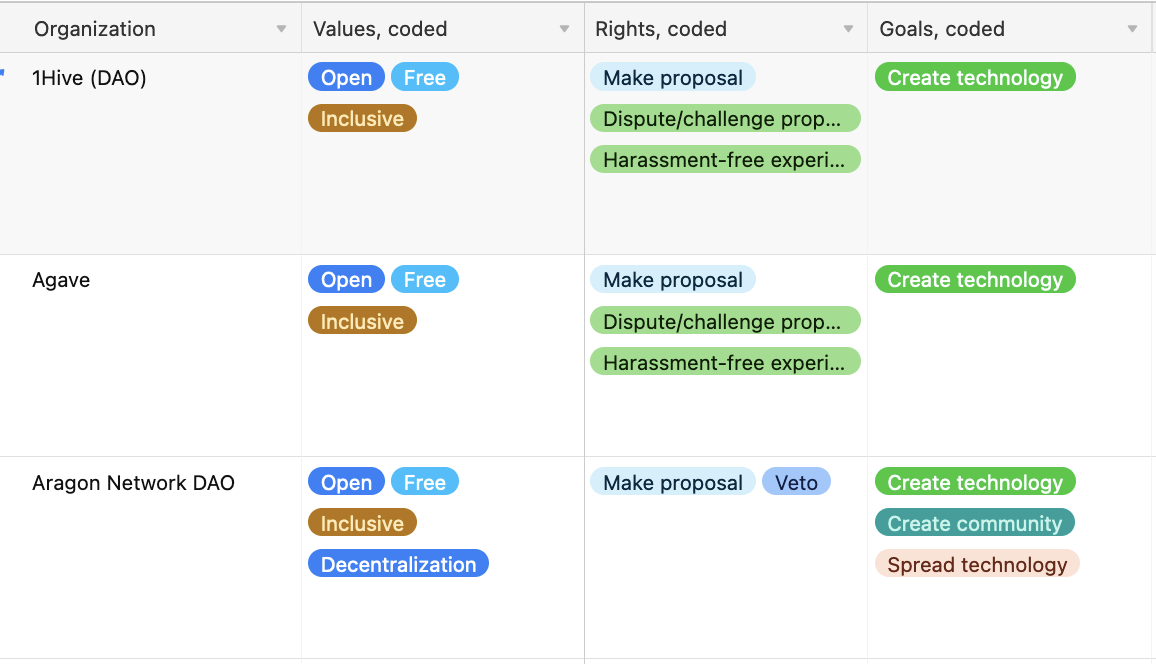

In cleaning and coding the raw dataset, we focused on capturing goals, values, and rights. Notably, we decided against trying to encode the rules and processes described in these documents not only because they were less salient in the documents we studied (see Part II) but because many of these young communities were still in the active process of determining or changing those rules and processes. We also incorporated several coding fields from the Comparative Constitutions Project (Elkins et al., 2010), including transprov, is_Amend, and in_Force, allowing direct comparisons between DAO constitutions and national constitutions along a number of dimensions. Other metadata include the title of the document, the date the constitution was created, aspects of its structure, and so on.

In coding for values, goals, and rights within a constitution, we first divided the document into sections following the top-level headers in the document, then matched different coded categories to each section (e.g. values are addressed in the “Our Values” section of the BrightDAO Charter, while rights are referenced in the “Our Mission”, “Our Vision”, and “Our Values” sections). In coding for these fields, we first collected the explicit words and descriptions used in the documents (e.g. “self-sovereign” or “sustainable decentralization”) and then mapped similar terms to a more restricted set of labels (e.g. “open”, “free”, “inclusive”, “professionalism”, and “decentralization”).

Part II: Analyzing DAO Constitutions

Open-source communities have a history of debating the terms of their engagement and arguing about what it is they are doing, as well as producing governance documents from contributor guidelines to governance.md files—practices which in turn bring the community into being. These documents give us a window into how communities imagine themselves and how they grapple with questions of purpose and coordination.

Governance documents include manifestos, constitutions, codes of conduct, community covenants, charters, and other genres with overlapping but distinct functions. These documents all outline a set of common values and goals with varying degrees of explicitness. They share many features with earlier texts within online groups ranging from open-source communities (Eghbal, 2020) to gaming communities (Mnookin, 1996). Governance documents in general are performative in the social scientific understanding of the term. Note that by ‘performative’, we do not mean that the constitutions are ornamental or do not serve a real purpose, rather that they enunciate the commitments of a group and serve to orient participants around a common project. For online communities, they also serve as an stable, anchoring feature of a space where the activities are fluid and participants can (typically) freely come and go.

We analyze governance documents as artifacts that use language to articulate ideas of technical and moral order specific to a project. A look at the language-specific elements of these constitutions can tell us about the social and moral dimensions of the projects they describe: how the community understands itself within an ecosystem of other actors, how it imagines its contribution, and against what forces it seeks to define itself.

The documents present a diversity of structures following a number of genres:

- Some are modeled on the modern notion of the constitution with separate "articles" that define specific subsets of rights and responsibilities.

- Others emulate the manifesto form with an expression of values and intent along with a set of guidelines to follow.

- Some read more like documentation to a software project.

- Yet others appear to be narrating a hero's journey (a narrative archetype popularly theorized by Joseph Campbell).

Each of these genres follow certain conventions and "do" certain things. Notably, they are more or less embedded in existing legal structures; for instance, the constitution of Ethereum World explicitly mentions Swiss law.

Beyond the structure or generic form of the documents themselves, the language of these constitutions further display a range of “registers,” or functional styles. Some are written in what would colloquially be called “legalese,” a register specialized to the legal profession which dumbfounds readers not versed in it. Others try to emulate “officialness” by using particles such as “shall” in an otherwise not specialized register. Some of the documents self-consciously marshal “kumbaya” type phrases and invocations, while others (notably, the ones following the 1Hive covenant template) are notably “plain,” that is, written in a register that is relatively unmarked by any specialized function. This has the effect of feeling the most inclusive, which perhaps explains why it has been emulated repeatedly.

These documents also invoke and address a number of different groups. The documents often speak in the voice of a first person plural, “we” (variously defined as “thinkers and doers,” “community of,” “members, contributors, leaders of”). They often articulate the intended beneficiaries of the project’s activities to be all of humanity (“all humans”, “humanity,” “individuals,” “the global society,” “everyone”), and they also frequently articulate the kinds of users and individuals which the project seeks to exclude. This is done implicitly by stating certain values (such as community over profit) or explicitly by naming (“malicious actors”). Future research may also wish to consider what the “we” represents within these documents, for example what is the intention of “we” and the function of this statement (for example, how the parameters of communities are made).

With some of the constitutions we observe references to other products and communities (in particular the ones that are based on the 1Hive community covenant) which locate the group at a particular place in a growing ecosystem. These references create intertextual links to other communities and governance practices, tools, and norms.

Constitutions describe goals, values, and rights

Following Redeker, et al. (2018) we identified the goals, values, and rights defined in each document (to the extent possible) and then coded them into overarching categories emergent from the texts. Our findings are significantly simpler compared to other frameworks for classifying digital rights and governance. This reflects both the relative simplicity of these early constitutional documents and the smaller size (and perhaps scope) of the political communities involved (cf. Davies, 2014).

Goals

- Create technology - the community aims to develop specific technologies related to Web3

- Spread technology - the community aims to spread in the sense of distribute this and related technologies in order to benefit the Web3 ecosystem

- Create community - the community aims to build a community devoted to the other goals

We have coded the goals that appear most frequently as “create technology,” “spread technology” and “create community.” These goals typify these communities as “recursive publics”: communities that come together in order to build the tools that allow them to come together as a community. In Kelty’s definition: “A recursive public is a public that is vitally concerned with the material and practical maintenance and modification of the technical, legal, practical, and conceptual means of its own existence as a public” (Kelty 2008, 3).

Values

- Open – allowing access to a product, community, environment

- Inclusive – aiming to provide access to the community for people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized

- Free – without cost or payment; not under the control of another

- Decentralization – not under centralized control, distributed

The values we have listed above can be encountered in these documents, however there is no standard definition of what each of these values mean to each of these communities. Each of these values can be understood as an open signifier, meaning that different DAO communities will attach different meanings to the same term. The values “free” and “open” initially served as open signifiers in free and open-source software communities but have conceptually stabilized over time as participants debated their meanings (Perens, 1998; Stallman, 2009). We are not surprised to discover that, as inheritors of this tradition, Web3 communities would center “open” and “free” in their governance documents.

The value “inclusive” is notable because it echoes long-standing commitments to meritocratic inclusivity in open-source software communities, but does so in a sociopolitical context in which “inclusivity” refers to social justice/identity politics issues more specifically. For example, the 1Hive constitutions promise, quite prominently, the “right to a harassment-free experience”. Further research is needed to understand how “inclusivity” is modeled and practiced beyond the value stated in the constitution.

Decentralization as a core value

Decentralization, although not a novel term, has gained a new salience with blockchain’s features and affordances. One of the central premises of these documents is to make a claim to “decentralization”. Scholars have generally agreed that there is no common definition for decentralization (Schneider, 2019) and in the context of blockchain, “decentralization” is the “boundary object”(Star & Griesemer, 1989) that enables individuals from different communities to work together. What is interesting about decentralization is that it has become a newly emergent term that now encapsulates various goals (serving as a means toward an end). Commitments to decentralization in blockchain spheres have now evolved into sophisticated bodies of thoughts and ideas. DAO constitutions hence serve as artifacts that embed some of these ideas and commitments to decentralization.

These documents provide a window into how communities understand decentralization and how its definition gets contested. The value of ‘decentralization’ hence dictates some of the conditions and precepts presented within these DAOs. It presents a particular narrative of how Web3 should operate (e.g. resistance to corporate power but not founder power).

A cursory examination of the contextual uses of the values indicate that their meanings vary despite being presumably stable. “Open,” another open signifier, doesn’t mean the same thing in each document. Further analysis is needed to map out patterns in the semantic fields of these terms, the relationships of values to rights and goals and to the types of DAOs (in particular, whether the DAO has a financial goal or not).

Rights

- Right to create proposal - The right to create proposal (usually by staking cryptocurrencies or governance tokens)

- Right to dispute/challenge proposal - The right to disagree with the proposers attestation by challenging the proposal (for example, through staking)

- Right to harassment free experience - No person will be discriminated based on their age, body size, visible or invisible disability, ethnicity, sex characteristics, gender identity and expression, level of experience, education, socio-economic status, nationality, personal appearance, race, religion, or sexual identity and orientation.

- Right to exit - The right to exit a community as a participant pleases, typically including the ability to withdraw assets when leaving.

Rights directly shape behavior by specifying permissible actions. In this sense, more so than values or goals, rights are highly consequential for governance. Within DAOs, rights are further distinct because of their correspondence with smart contracts. Because they do no possess the expressive power of language, smart contracts are a poor medium for capturing values or goals

Within the documents in our dataset, ‘rights’ are defined more uniformly and precisely than ‘values’ or ‘goals’. The right to create proposals, for instance, refers to an action that is much more specific than, for example, than ‘decentralization’ or ‘open’ as a stated value. We hypothesize that this has to do with the affordances of the smart contract; in order to interact with a smart contract, a right needs to be specified in technically-precise language. In other words, rights have to be translated into code to be put on-chain, and vice versa, a right that already exists on-chain can be translated into precise language. A more prosaic reason for the uniformity of stated rights is that there is substantial copying and forking between DAO constitutions, e.g. a few constitutions in our data set were derived from 1Hive’s constitutional template.

As the social and technical infrastructure around digital governance improves, we hope and expect to see the breadth of rights broaden. The rights so far are few in number and similar in theme. We hope to see rights become broader and more useful.

Part III: Towards Computational Constitutionalism

A digital constitution, extending Redeker et al.’s definition, is a text that articulates a set of political rights, governance norms, and limitations on the exercise of power within an online community. So far, we have created a data set of digital constitutions (among other governance documents) of DAOs and related Web3 entities, coded the goals, values, and rights present in these texts, identified their major functions and themes, and made several recommendations for useful constitutions based on our findings. But as we noted in the introduction, DAOs are defined by their usage of smart contracts. These smart contracts are computational constitutions insofar as they encode rights, norms, and limitations on the exercise of power within the DAO (Zargham et al. 2020)

Relating digital and computational constitutions

While there are clear patterns across digital constitutions, those texts are still relatively bespoke to the communities that write them. In contrast, the smart contracts used by most DAOs are not bespoke; the specialized technical knowledge required to write functional and secure smart contracts precludes most DAOs from creating theirs from scratch. As a result, a number of templates and "DAO factories", produced by external organizations, have emerged to help DAO creators deploy the core smart contracts of a DAO with a specified set of configurable parameters. The distribution of templates used by DAOs in our dataset is shown below

Much work remains to be done to understand the relationship between these smart contracts and “off-chain” institutional constructs such as a constitution. While smart contracts neither need nor assume constitutions (and vice versa), the value of understanding DAOs through the lens of computational constitutionalism is to see how certain rights and certain forms of governance can be more easily and effectively provided by a smart contract, by a constitution (and constitutional norms), or by some combination of the two. As we have seen, the textual constitutions commonly articulate rights already guaranteed by the smart contracts, including proposal creation and proposal dispute as well as voting, veto, and exit. But to what extent should constitutions reference the smart contract? In what cases should a written constitution or charter defer to the contract, and in what cases should the contract defer to the constitution?

To understand how governance smart contracts function on their own and in conjunction with textual constitutions or other governance documents and processes, we must investigate three distinct data sets:

- the rights and affordances defined within the template smart contracts,

- the parameter configurations with which DAOs have chosen to deploy their own computational governance systems from template smart contracts, and

- the resulting governance activity circumscribed by the smart contracts.

These data sets will allow us to investigate what framework designers have considered necessary and sufficient to implement governance on a blockchain, what DAOs leaders have considered necessary and desirable to implement governance on a blockchain, and what governance actions DAO members actually take within the constraints of the governance configuration. Ultimately, understanding these will allow for the creation of theoretical frameworks and practical tools for design and configuration patterns in the computational governance of online communities.

We defer a detailed analysis of the parameters and behavior of the smart contracts themselves to future work.

Future work

Beyond analyzing smart contracts, there is still much work to be done to expand the dataset of textual documents and to contextualize their creation and use. We hope to continue building our dataset not only by lowering the friction of contributing data but also by automating certain aspects of data collection, especially through improvements to our template or to the associated tools and widgets in the code repository.

Additionally, further information is needed to understand the relationship between the structure and contents of a textual constitution and its observed usage in governing a community. For what audiences was the constitution written, and how does its publishing location relate to these? What are the processes by which the constitution was created, and who was involved in its drafting and revision? In what ways and with what frequency is the constitution being referenced and revisited by the community it governs?

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jacky Zhao, Jasmine Wang, and Evan Miyazono. This work was made possible through a grant from the Filecoin Foundation. Joshua Tan was also funded through the EPSRC IAA Doctoral Impact Scheme and the Stanford Digital Civil Society Lab.

Bibliography

Campbell, J. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library.

Davies, T. (2014). Digital Rights and Freedoms: A Framework for Surveying Users and Analyzing Policies. In L. M. Aiello & D. McFarland (Eds.), Social Informatics: 6th International Conference, SocInfo 2014, Barcelona, Spain, November 11-13, 2014. Proceedings (pp. 428–443). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13734-6_31

Eghbal, N. (2020). Working in Public: The Making and Maintenance of Open Source Software. Stripe Press.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2010). The Comparative Constitutions Project: A Cross-National Historical Dataset of Written Constitutions. 170.

Mnookin, J. L. (1996). Virtual(ly) Law: The Emergence of Law in LambdaMOO: Mnookin. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 2(1), 0–0. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1996.tb00185.x

NewsDemon.com. (2022, July 4). All Usenet Charters List. NewsDemon.Com – Usenet Newsgroups. https://web.archive.org/web/20220704170238/https://www.newsdemon.com/charter-directory

Perens, B. (1998). The Open Source Definition. Linux Gazette.

Redeker, D., Gill, L., & Gasser, U. (2018). Towards digital constitutionalism? Mapping attempts to craft an Internet Bill of Rights. International Communication Gazette, 80(4), 302–319. https://doi.org/10/gdk37x

Schneider, N. (2019). Decentralization: An incomplete ambition.

Journal of Cultural Economy, 12(4), 265–285. https://doi.org/10/ggf7m3 Stallman, R. (2009). Why “open source” misses the point of free software. Communications of the ACM, 52(6), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1145/1516046.1516058

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional Ecology, `Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

Tan, J. Z., Korpas, L., & Brody, A. (2022, January 16). Where do you belong in crypto? The Metagovernance Project. https://medium.com/metagov/the-political-landscape-of-crypto-f440d521f411

Zamfir, V. (2019, January 29). Against Szabo’s Law, For A New Crypto Legal System. Crypto Law Review. https://medium.com/cryptolawreview/against-szabos-law-for-a-new-crypto-legal-system-d00d0f3d3827

Zargham, M., De Filippi, P., Tan, J. Z., & Emmett, J. (2021, March 24). Exploring DAOs as a new kind of institution. Commons Stack. https://medium.com/commonsstack/exploring-daos-as-a-new-kind-of-institution-8103e6b156d4